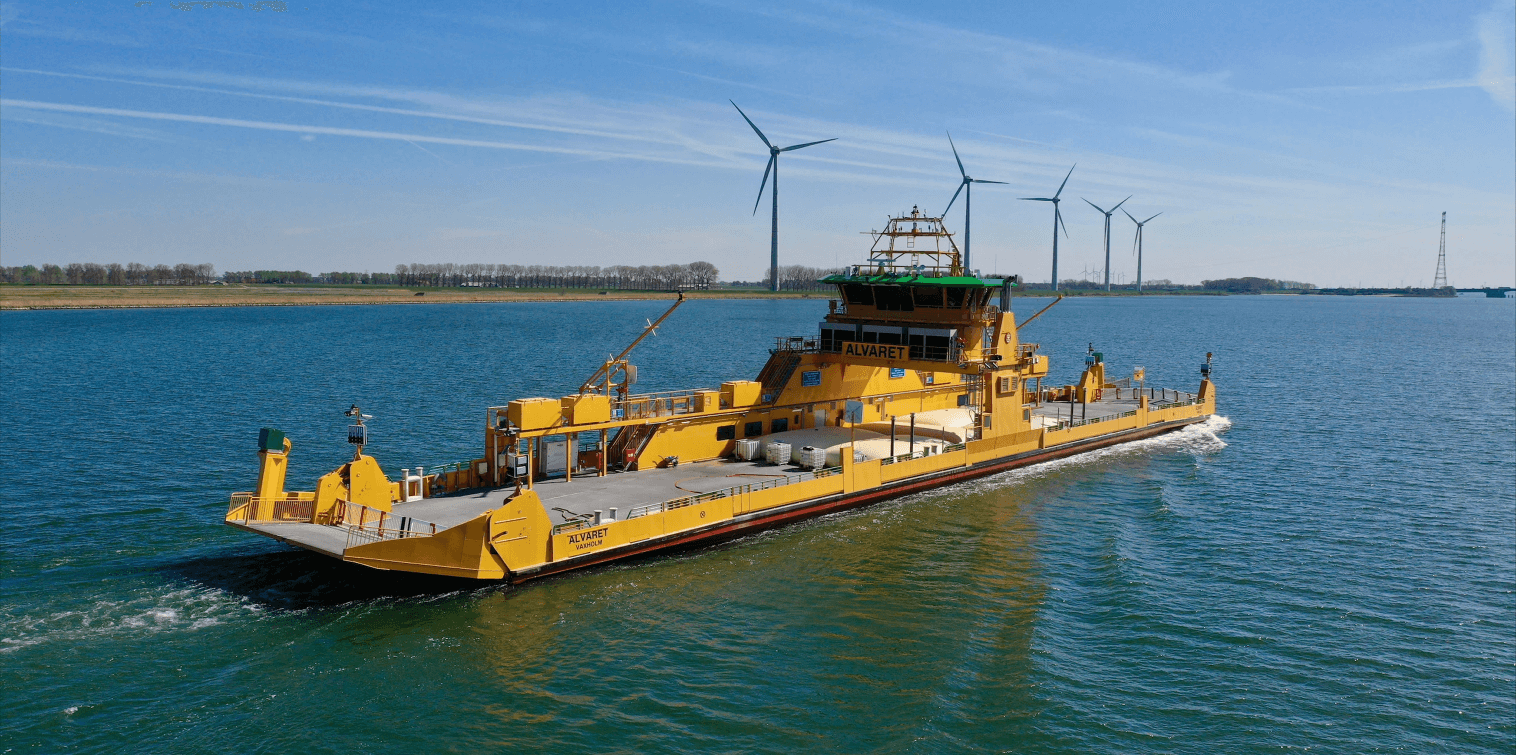

Building smart, specialised vessels: how Holland Shipyards Group turns customer questions into practical innovation

Looking ahead

Holland Shipyards Group is scaling, taking on larger and more complex vessels and building expertise in autonomy and practical sustainability. “We are not chasing trends,” Shanna concludes. “We focus on what our clients need and how we can help them operate better.”

In that combination, openness, collaboration and constant improvement, the company is strengthening the wider maritime ecosystem that connects to Rotterdam, while delivering specialised vessels for the next phase of European operations.

Interested in connecting?

Follow Holland Shipyards Group via LinkedIn or get in touch through their website.

All photographs are courtesy of Holland Shipyards Group.

Shaping sustainable shipping: innovation, people and partnerships in Rotterdam

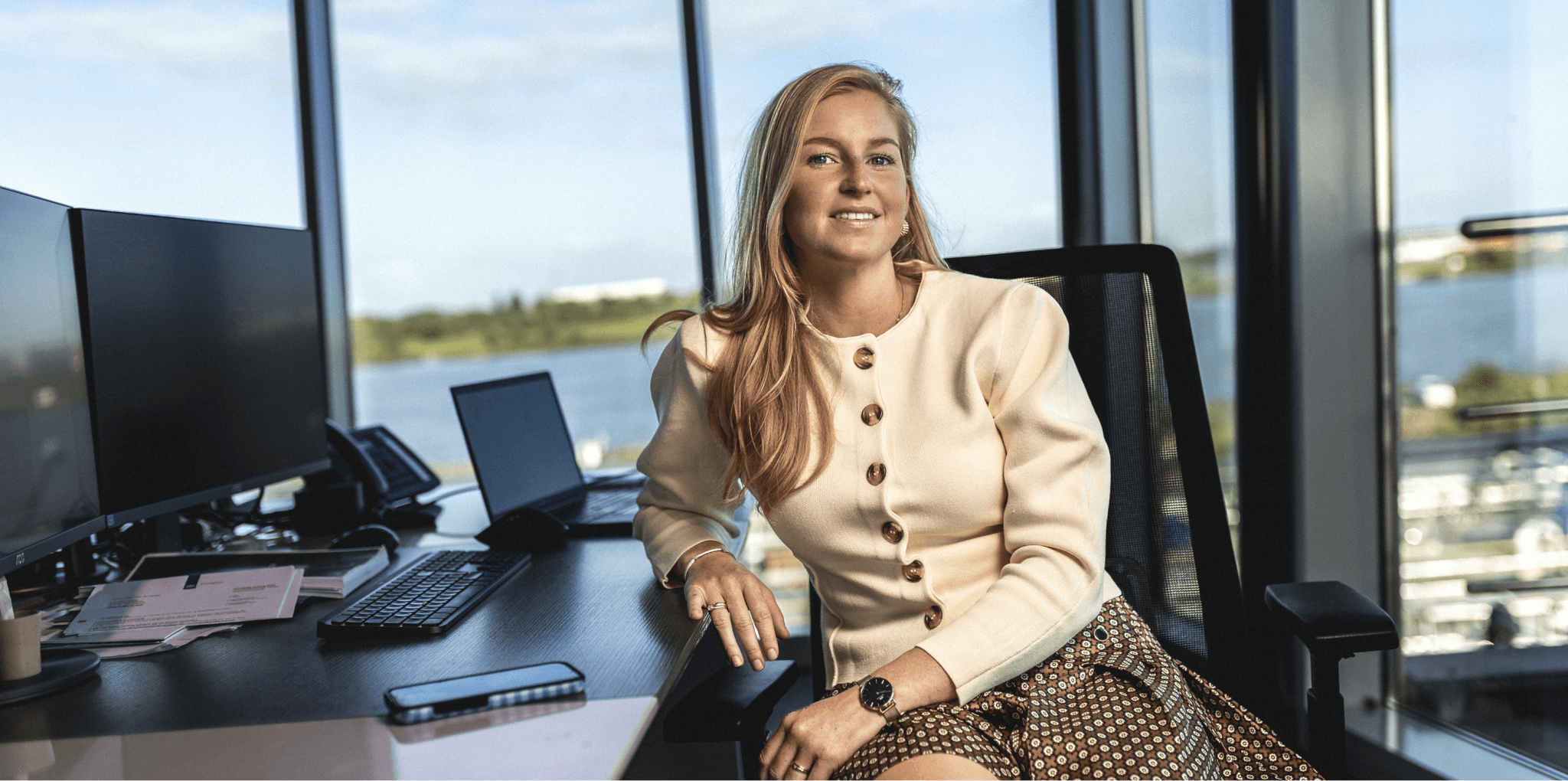

Charting her own course: Heleen Kornet on leadership, legacy and navigating a male dominated maritime world

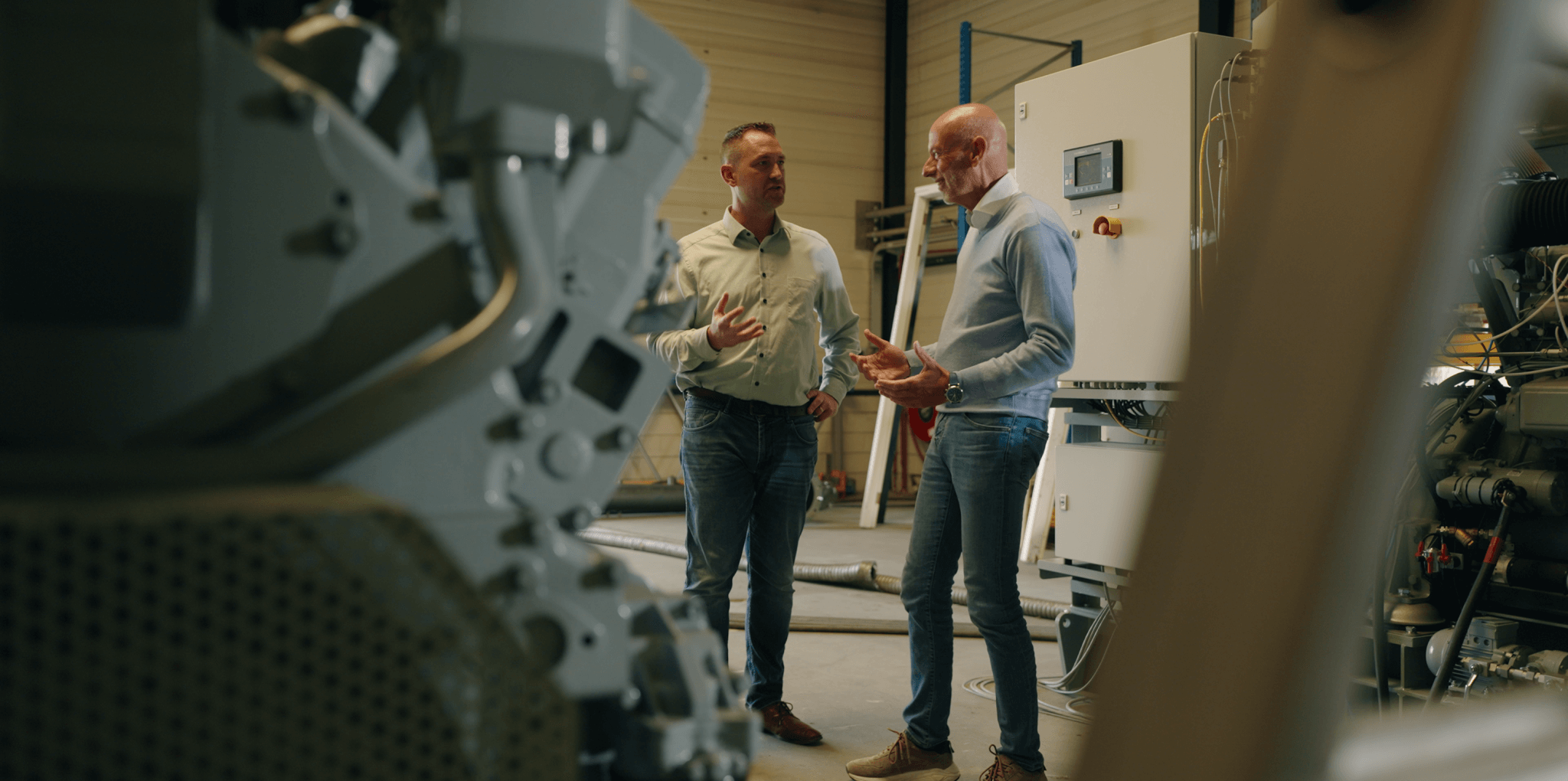

Innovating inland shipping: how Concordia Damen strengthens the maritime ecosystem from Werkendam to Rotterdam

Working with trust and curiosity: Shanna van Berchum on building a career in the maritime industry

Beyond the engine: testing methanol for cleaner shipping